Using lotteries to increase fairness and efficiency in research assessment

13 March 2025

Queensland University of Technology

Photo by dylan nolte on Unsplash

When the reasons run out

Football matches (England)

Places on medical degrees (Sweden, The Netherlands)

Military conscription (USA, Australia)

Athenian democracy

Kleroterion

Immanuel Kant

“The first task of reason is to recognize its own limitations.”

Perfect ranking is impossible part 1

Perfect ranking is impossible part 2

Luck of the draw of the reviewers

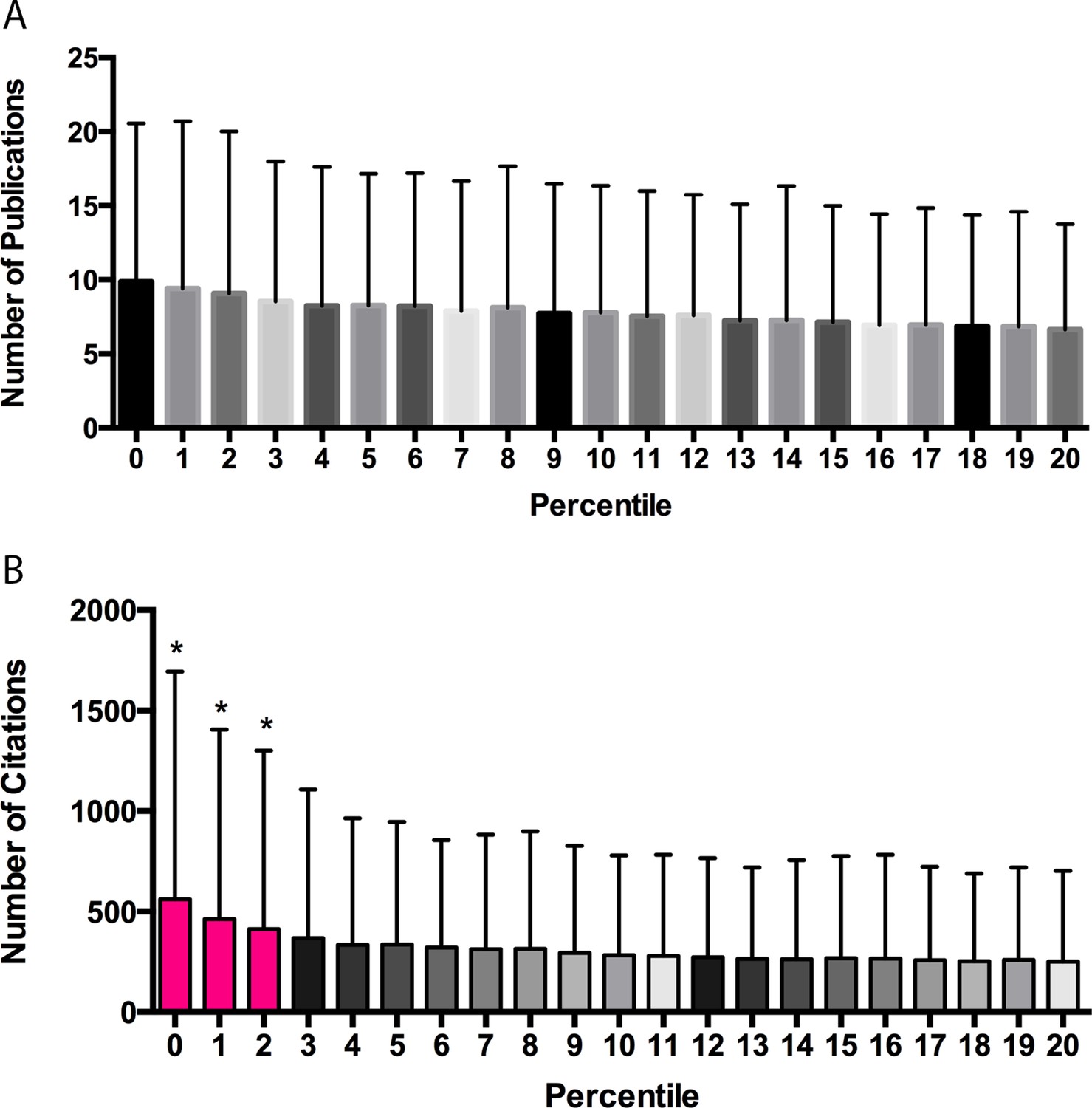

Australian data:

- 9% grant proposals were always funded

- 29% sometimes funded

- 61% never funded

Katalin Karikó

- Outlandish idea to use messenger RNA as a medicine

- Research opportunity with funding for six scientists from seven applications

- Karikó’s was the only one that wasn’t funded

Inefficiency

Szilard point: the expenses incurred in obtaining a grant are equal to the value of the awarded grant

ACSPRI fellowship with 100 and 160 applications and only one award of $25,000

J&J fellowship for women in STEM, 650 applications and 6 awarded

Who has used a lottery?

- Health Research Council of New Zealand

- VolkswagenStiftung

- Austrian Science Fund (FWF)

- Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF)

- Novo Nordisk Fonden

- British Academy

- UKRI / NERC

- Wellcome

- Nesta

- University of Leeds

- UMC Utrecht/Ministry of OCW

- UKRI

- Carnegie Trust

- Statistical Society of Australia

- Association for Interdisciplinary Meta-Research and Open Science (AIMOS)

- International Society for Clinical Biostatistics (ISCB)

New Zealand Health Research Council

Fellowship was NZD $150,000 (£70,000) over 3 years

Two yes/no criteria:

- the research is potentially transformative

- the proposal is exploratory but viable

Randomised if most reviewers gave two Yes’s

Survey of applicants

- Randomisation is an acceptable method, with 63% in favour and 25% against

Researchers wanted ineligible applications to be excluded and outstanding applications funded, so the remaining applications were truly equal

Greater support for randomisation amongst those that won funding at random

Photo by Thom Milkovic on Unsplash; DOI: 10.1186/s41073-019-0089-z

Priority setting on research funding

Top 2 questions:

Would a lottery be fairer and more efficient without reducing quality?

How much is enough effort for applying + judging application efforts, before a random lottery-style allocation becomes just as good as further adjudication?

Arguments against using a modified lottery

Rewards less deserving and/or less enthusiastic

Encourages less talented to apply

Applicants put in less effort

Potential benefits

- Reduces cronyism (and perception of cronyism)

Increases diversity in applicants and winners

Reduces application and review costs

Acknowledges that science is unpredictable

Reduces stigma of failure

Might reduce “Matthew effect”

Applicants might try more innovative ideas

Creates a perfect randomised trial of funding

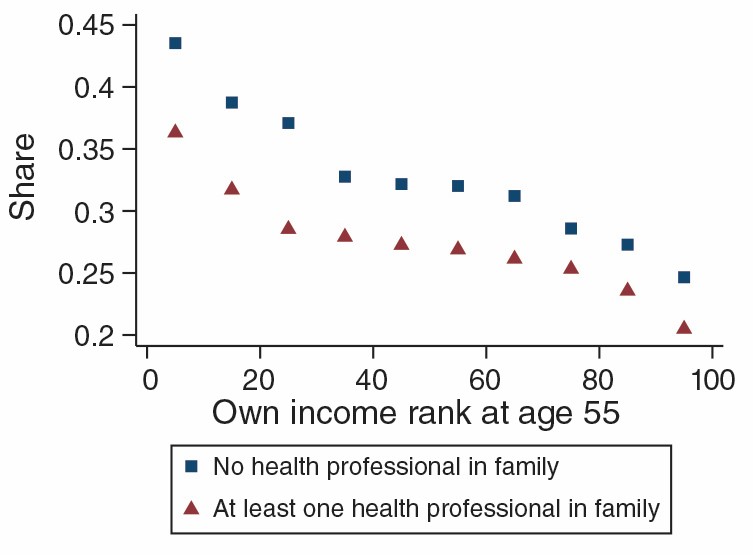

Lotteries create ideal trials

“Having a doctor in the family raises preventive health investments throughout the life cycle, improves physical health, and prolongs life.”

Bad publicity

Summary

Complex application systems may feel thorough, but they are costly and potentially amplify biases

There will never be a perfect system for the incredibly difficult task of accurately allocating research funding

Lotteries can be the most scientific approach